Redefining arrhythmia treatment

Catheter ablation, OPTION and Brain-AF.

Saturday’s Late-Breaking Science session “Redefining Arrhythmia Treatment: Pushing Boundaries” found that:

- Catheter ablation tops antiarrhythmic drug therapy to block VT in ischemic cardiomyopathy.

- OPTION showed left atrial appendage device beats oral anticoagulation for bleeding after AF ablation.

- No cognitive impairment or stroke benefit from oral anticoagulation seen in BRAIN-AF.

The first large head-to-head trial of catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drug therapy to suppress ventricular tachycardia (VT) following myocardial infarction (MI) suggested ablation is the preferred first-line therapy for patients who have persistent VT with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). The VANISH2 trial showed a 25% benefit for ablation (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.58-0.97, p=0.03) without major differences in safety compared to antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Patients were followed for a median of 4.3 years. John Sapp, MD

John Sapp, MD

“In terms of serious adverse events, there was no statistically significant difference, although the trend was toward better survival following catheter ablation" said John Sapp, MD, professor of cardiology at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada. “We observed the anticipated drug side effects and procedural complications.”

Cardiac arrhythmia that stems from electrical dysfunction across ischemic scars is one of the most common causes of sudden death in individuals who have had one or more prior MI’s, Sapp said. VT is the most common arrhythmia leading to sudden death in the days to weeks and years following MI.

The VANISH1 trial established the superiority of catheter ablation vs. escalation of drug therapy in patients with VT despite antiarrhythmic drug therapy but did not address first-line treatment.VANISH2 randomized 416 patients in North America and Europe with prior MI and clinically significant VT, defined as VT storm, appropriate ICD shock, recurrent anti-tachycardia pacing or sustained VT presenting for emergent treatment. Patients received either catheter ablation (203 patients) or drug therapy (213 patients) with sotalol or amiodarone as initial therapy. Ablation was performed within 14 days of randomization.

The primary endpoint was a composite of death or, ≥ 14 days after treatment, VT storm, appropriate ICD shock or sustained VT that presented for emergent treatment emergently.

The primary endpoint was seen in 50.7% of patients who received ablation and 60.6% of those who received drug treatment, a 9.9% absolute reduction and 25% relative reduction for ablation.

Among patients randomized to ablation, death was observed in 1.0% of patients, nonfatal stroke in 1.0%, cardiac perforation in 0.5% and vascular injury in 1.9%. Among patients randomized to drug treatment, one died due to pulmonary toxicity and 21.6% experienced non-fatal drug-related adverse events.

While VANISH2 clearly demonstrated a benefit for ablation versus antiarrhythmic drug therapy as first-line treatment for ischemic cardiomyopathy, the trial did not address other, nonischemic causes of VT. Sapp noted that VT resulting from cardiac scarring other than MI can be more difficult to treat with ablation than VT associated with MI scarring.

“We still need to understand how best to treat patients with VT who have nonischemic cardiomyopathy,” Sapp said. “The outcomes for ablation may be different in that population and the relative benefits and risks could therefore be different as well.”

VANISH2 was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Left atrial appendage closure beats oral anticoagulation for bleeding after catheter ablation

The first direct comparison between oral anticoagulation and left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) using the WATCHMAN implant after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation (AFib) found significantly less major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, 8.5% for LAAC versus 18.1% for oral anticoagulation. The closure device was statistically non-inferior to oral anticoagulation for a composite endpoint of all-cause death, stroke or systemic embolism at 36 months (5.3% vs. 5.8%, respectively, p for noninferiority <0.0001) with a numerical trend for superiority. Oussama Wazni, MD, MBA

Oussama Wazni, MD, MBA

“This has the possibility of changing clinical practice,” said Oussama Wazni, MD, MBA, head of electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic. “I think people are going to want to close the left atrial appendage and not have to worry about anticoagulation, especially because the difference in bleeding rates was so high.”

OPTION randomized 1,600 patients across 114 global sites, 803 patients to LAAC and 797 to OAC. Patients were 69.6 years old and had a mean CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3.5. LAAC was performed in combination with (40.8%) or sequentially after (59.2%) catheter ablation for AFib.

The primary safety endpoint was nonprocedural major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding at 36 months. Major bleeding, including procedural bleeding, through 36 months, was a secondary endpoint.

LAAC was successful in 99% of patients, Wazni reported. The rates of major bleeding were comparable, 3.9% for LAAC versus 5.0% for OAC, p for noninferiority < 0.0001, with a numerical trend favoring LAAC.

“For all intents and purposes in patients who undergo an ablation for AFib and have a moderate to high risk for stroke, most of them are probably going to end up with left atrial appendage closure,” he said.

OPTION was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

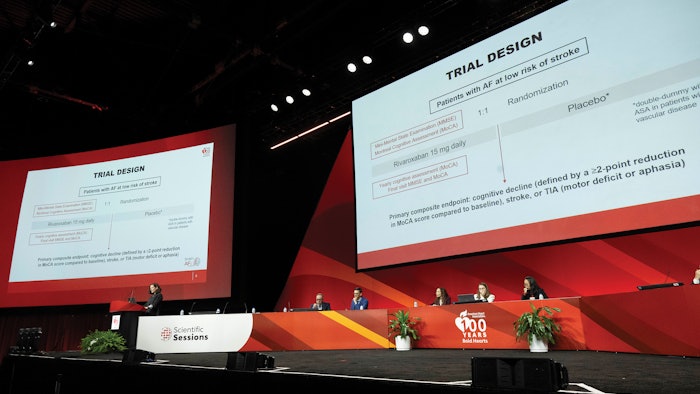

BRAIN-AF halted early

The BRAIN-AF trial of anticoagulation to prevent ischemic stroke and neurocognitive impairment in low-risk individuals with AFib was halted early for lack of benefit. Anticoagulation with rivaroxaban 15 mg/day did not reduce the incidence of cognitive decline, stroke or TIA in patients in their 50s who had AFib but no conventional risk factors for stroke.

“We have been seeing reports for the last 10-15 years showing a link between atrial fibrillation and cognitive decline and dementia. Whether the link is causal or due to shared risk factors remains unknown. But cerebral emboli damaging the brain is one of the main hypothesis, said Lena Rivard, MD, MSc, Montreal Heart Institute in Montreal, Canada. “And in our own clinical practice, we have been seeing patients in their 50s, very young, without any stroke risk but who had both atrial fibrillation and cognitive decline.” Lena Rivard, MD, MSc

Lena Rivard, MD, MSc

BRAIN-AF followed 1,235 patients with atrial fibrillation and low risk for stroke, no congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/TIA or age ≥65 years. Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 15 mg/day or standard care, either placebo or aspirin, depending on vascular status. Median age was 53.4 years and 25.6% were female. Patient underwent yearly cognitive testing. More than 5,500 Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tests were performed during the trial.

The primary outcome was a composite of stroke, TIA or cognitive decline as measured by a decline in MoCA score ≥2. The trial was planned to continue until 410 primary events occurred but was halted for futility after 205 events following a planned interim analysis. Median follow-up was 3.7 years

In intention-to-treat analysis, the composite primary event was observed in 130 patients in the rivaroxaban group, 7% per year, versus 126 in the usual care group, 6.4% per year, p=0.46 (95% CI 0.86-1.40). There were no differences in the primary outcome components. The study was not powered to test anticoagulation therapy in stroke, TIA and systemic embolism. The combined secondary outcome of stroke, TIA or systemic embolism occurred in 2.5% of patients randomized to rivaroxaban and 2.7% of patients randomized to placebo (HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.50-1.84).

“We didn’t have any safety issues, which is very reassuring,” Rivard said. “Major bleeding occurred in just two patients on rivaroxaban (0.03%) and five on standard care (0.08%). Biomarker, cerebral MRI and genetic testing results will be presented later.”