Q&A: The pursuit of receptors for adrenaline

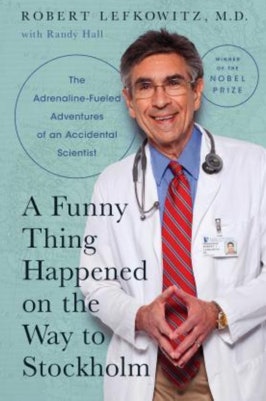

Robert J. Lefkowitz, MD, FAHA, co-recipient of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on G-coupled protein receptors, will deliver the Distinguished Scientist lecture.

The Daily News spoke with Robert J. Lefkowitz, MD, FAHA, co-recipient of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on G-coupled protein receptors, which allow the body’s cells to sense and respond to internal and external signals, such as flavors, taste, smell, odor, light and danger. GCPRs are now the target for numerous modern drugs. Dr. Lefkowitz promises to recap “50 years of research in 50 minutes” during the Distinguished Scientist Lecture. For this interview, Dr. Lefkowitz, the James B. Duke professor of medicine at Duke University, expounded on the importance of clinician-scientists, spoke of his esteem for the American Heart Association and gave us a peek into his new book.

He will present his Distinguished Scientist Award on G-protein coupled receptors 3:30-4:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 14.

Q: The Distinguished Science Lecture is one of many awards you’ve received from the AHA. What do the American Heart Association and Scientific Sessions mean to you?

Dr. Lefkowitz: The first value that the American Heart Association has had for me is that it is responsible for my one and only job. When I was a young fellow in cardiology at Mass General Hospital in Boston from 1971 to 1973, I gave two presentations at the AHA, one in 1971 and one in 1972.

The chief of cardiology at Duke, Andrew Wallace, heard those presentations and was sufficiently impressed that he invited me down to Duke to have a look at a job heading up a new program called “molecular cardiology,” which as a discipline did not yet exist. I was initially reluctant. The idea of moving that far south was not attractive to me. I thought I would take the job for five to seven years, hopefully begin to make my mark and then move back to the northeast. But, in fact, I fell in love with the area, my research took off, and voila! I’ve stayed the rest of my career.

Beyond that, I really enjoy the AHA meetings. They are fantastic in terms of their depth of science — both basic, fundamental research through the latest in clinical science.

Q: What advice do you have for young cardiologists?

Dr. Lefkowitz: I would suggest that they really try to incorporate an element of scientific research investigation into their careers. It doesn’t have to be basic bench work; it could be clinical research or somewhere in between — translational research. If you want to have a long career, I think it’s fun to have different aspects to it. You know, a lot of clinical work eventually becomes very repetitive. I mean, when you’ve seen your 200th patient with heart failure, or your 500th with hypertension, you don’t have to think about it a lot — you pretty much know reflexively what to do. But the research laboratory — be it the clinical or the basic — is the opposite. Every day is different, every experiment is different, every question is different. It keeps things a little livelier.

Q: As a card-carrying physician-scientist, could you comment on the state of physician-scientists today? In 1979, Dr. James Wyngaarden called them an endangered species. What’s it like now?

Dr. Lefkowitz: Worse. He was the first one to call attention to the declining number of physician-scientists. He was my first boss, because he was chair of medicine at Duke, when Andy Wallace, the chair of cardiology, came looking for me. Dr. Wallace worked for Dr. Wyngaarden. That was more than 40 years ago, and he was, astutely, the very first person to sound the alarm. The reason I helped start the Physician-Scientist Support Foundation is that the problem has grown progressively worse, and fewer and fewer physicians are becoming physician-scientists. Nothing more acutely or vividly shines a spotlight on the importance of physician-scientists than the pandemic, with Tony Fauci being the poster child for physician-scientists, and how important they are, especially in times of crisis like this.

Q: Do you think more people will become physician-scientists because of Dr. Fauci?

Dr. Lefkowitz: I do believe that. I think a lot of young people are being inspired by Tony, to say, “Wow! What an amazing career, what an amazing opportunity to apply scientific and medical knowledge to the benefit of humanity.” I’m quite certain there will be a large number of young people who are going to be drawn into such a career. I know for a fact that last year the number of applications to medical school was the largest that it has been either in history or in many, many years.

Q: Your book A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm: The Adrenaline-Fueled Adventures of an Accidental Scientist came out in February. How did that come about?

Dr. Lefkowitz: A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm — that’s obviously patterned after [the 1962 Broadway musical] “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.” I like that because I’m basically a funny guy, and if you’ve read the book, you know there are lots of humorous stories in there that reflect my approach to life, which is filled with humor.

The second part of the title, The Adrenaline-Fueled Adventures of an Accidental Scientist — the adrenaline part, it turns out adrenaline is a big part of my research. I worked on receptors for adrenaline, but the key part is “accidental scientist.” I never intended to be a scientist. From the

When I graduated from medical school in 1966, the Vietnam War was raging and in addition to a lottery draft for all men over 18, there was a non-lottery draft, conscription, for all male physicians, so 100 percent of male physicians on graduation from medical school in the 1960s went into the Armed Services for two years. They would give you a two-year deferment after graduation to get some further clinical training and then you went into the Army, the Navy, the Air Force or the Public Health Service, and you spent one of your two years, pretty much, in Vietnam. It was a very unpopular war — but there were very few legal ways out. One of the few was to be drafted into the Public Health Service because they had some stateside assignments, like the NIH and the CDC and other research institutions. So, of course, everyone wanted to get into the Public Health Service, and it was very competitive, and they had their pick of the best and the brightest. Fortunately, I had very high grades and recommendations. I and a number of others were drafted into the Public Health Service and assigned to the NIH where we began doing research. And after a miserable first year or year-and-a-half where absolutely nothing worked for me, I began to have some success and get the bug. So, the “accident” for this accidental scientist was the Vietnam War and my being drafted into the Public Health Service and being assigned to the NIH.

Had I not had that experience, I undoubtedly would never have gone into research and would have happily spent my life practicing medicine and cardiology. The remarkable thing is just how successful that program was in producing my entire generation of physician-scientists, academicians, professors of medicine and deans of medical schools. In my class — those of us from 1968 to 1970, maybe 100 people — four of us, all physicians, with really no prior research training, would go on to win the Nobel Prize, which is insane. So it turns out between 1964 and 1972 — eight peak years of the Vietnam War — there was this program, which came to be called somewhat derisively the “Yellow Berets.” You have the Green Berets and their bravery, and you have the Yellow Berets who are fighting the “Battle of Bethesda,” so to speak. Of this Yellow Beret program, 10 of us would go on to win the Nobel Prize, and the program would produce virtually my entire generation of professors and deans of medicine.

Q: Did you have the choice of your laboratory?

Dr. Lefkowitz: We were assigned a lab. There was a matching system. The one I got was not the one I wanted. I was looking for a much more cardiovascular-oriented lab.

I knew in medical school that I wanted to do cardiology. That was to a big extent influenced by the fact that my father and mother had premature coronary artery disease. But instead, I ended up in a lab at the NIH that did endocrinology. As it turns out, this was another fortunate piece of serendipity for me because the techniques I learned from the endocrinology people were very biochemical and molecular, which was not a part of cardiological research at the time. So, I was then able to see the value of applying biochemical and endocrinological approaches — like receptors — to the CV system. I think that helped jumpstart my career.

Q: That, and the AHA?

Dr. Lefkowitz: Yes. I am very honored to receive another wonderful award from the AHA. They have been wonderful in honoring me over the years. Every time I get one of these awards or give an honorary lecture here, it always draws me back to the very beginning in my career and how I got my job by virtue of presenting at the AHA, so I always I have very warm feelings toward the organization.

Visit Scientific Sessions Conference Coverage for more articles.