Overcoming adversity and related poor health from birth to adulthood

AHA president details reality and solutions.

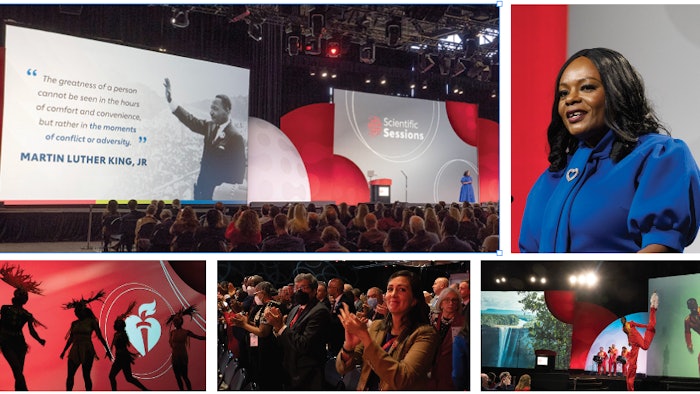

Combatting the effects of adversity on a person’s physical health is a lifelong struggle, said Michelle A. Albert, MD, MPH, FACC, FAHA.

Dr. Albert, cardiologist and American Heart Association president, delivered the grim reality and supporting statistics during Sunday’s Presidential Session’s Conner Lecture. She has spent a decade studying how adversity translates into clinical medicine — more specifically, cardiovascular health. Her work focuses on biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk and social determinants of health, especially among women and people of underrepresented groups.

“Adversity is a state of persistent difficulty, calamity or misfortune that affects one’s ability to achieve various life goals, including health outcomes, well-being or happiness,” said Dr. Albert, who as AHA president serves as chief science volunteer and presides over the association’s Science Advisory & Coordinating Committee.

Citing violence, racism, crime, natural disasters, COVID-19 and economic distress as examples of adversity across the globe, Dr. Albert’s address detailed “the biology of adversity and how economic adversity underpins it all.”

Cardiovascular — and all clinical outcomes — can be modified, for better or worse, by a person’s resilience and traditional risk factors that can’t always be controlled. However, a more positive and lasting influence is available through a person’s wealth, Dr. Albert said. And she’s not just talking about money.

“In this context, wealth can be finances, social capital or support or even joy,” said Dr. Albert, the Walter A. Haas-Lucie Stern Endowed Chair in Cardiology and Professor in Medicine Admissions Dean for the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine and founding director of the Center for the Study of Adversity and Cardiovascular Disease.

“Wealth is the currency that can help counter the experience of adversity.”

Understanding these interconnections is an important first step, Dr. Albert said, but not without further insight. For example, racial and ethnic discrimination is an all-too-common form of adversity that Dr. Albert refers to as a “discrimination iceberg.” She said about one-third of discrimination is the tip of the iceberg — readily observable or overt. This includes things such as hate crimes. However, two-thirds of the “dangerous majority” occurs below the surface of the iceberg, or is covert, she said. This includes structural racism and implicit biases.

“Research shows significant associations of everyday discrimination with surrogate biomarkers of cardiovascular disease, such as elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, coronary artery calcification, hypertension as well as low birth weight, poor sleep and with outcomes such as cognitive impairment and mortality,” she said.

The biology of adversity can be a lifelong struggle, beginning in utero and the effects of which can be passed on via epigenetic mechanisms. Add to that the potential for adverse maternal experiences such as depression, economic issues and low social status, and these adverse childhood experiences (ACES) can lead to poor cognitive outcomes and cardiovascular disease. The most common ACE, however, is economic adversity, Dr. Albert said.

“I believe economic adversity is a root cause of health inequities and disparities,” she said.

The top 1% of people in the U.S. have nearly 20 times greater wealth than the bottom 50% of the global community, Dr. Albert said. About 12% of people have difficulty paying medical bills. This includes 20% of middle-income people. The statistics are “jarring,” she said.

“Clearly, this makes the playing field uneven, and economic progress nearly impossible as it limits intergenerational wealth and health,” Dr. Albert said. “You might be thinking education could help bridge that gap. But it is not that simple.”

Though education increases a person’s wealth, the returns aren’t the same for everyone. In fact, Black people must have a post-graduate degree to attain similar wealth as white people with a high-school degree, Dr. Albert said.

As daunting as these health disparities are, Dr. Albert said that not everyone enduring adversity will experience poor health outcomes. Still, she said there’s hope. Cardiology researchers and clinicians can make a difference, whether it’s writing a grant, raising awareness through public speaking, partnering with private and community organizations or participating in legislative advocacy.

“I want to empower you to see yourself as part of the solution,” she said. “You can be part of the movement toward ensuring education and employment in a way that will improve generational wealth and health. It starts with committing to making a difference. We need not let people die from the effects of economic adversity. You can make a difference by supporting innovative ideas.”